Jungheinrich exclusively relies on green electricity in the future

28. February 2021DPDgroup Reports Record Year 2020 and Five-Year Strategy

1. March 2021The Swiss economy is significantly dependent on international goods transport by sea. The sea may seem far away for most Swiss people – but shipping and its transport capacity are essential for the Swiss Confederation. The Logistics Advisory Experts GmbH (LAE), a spin-off from the University of St. Gallen, found with a team led by Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Stölzle that more than 90% of the imported and exported goods of Swiss foreign trade are transported internationally by sea.

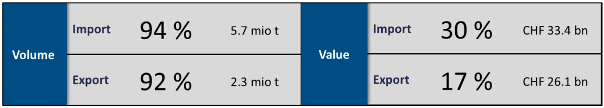

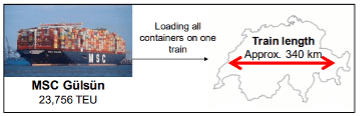

(Arbon) – Maritime shipping plays no role in the official statistics of the Federal Customs Administration (FCA) – ships are not registered as transport carriers for the import and export of goods to and from Switzerland. Nevertheless, the transport performance in international trade cannot be dispensed with. The study “Switzerland’s dependency on maritime transportation” commissioned by the Swiss Shipowner Association (SSA) found that about 92% of the total extra-European export volume measured in tons is transported by sea to the wider world. In imports, even 94% of goods are transported by sea across the oceans, to later cross the border into Switzerland by inland ship, truck, or rail (see Figure 1). Despite the lack of sea access, the transport of goods by deep-sea vessels is thus indispensable for Switzerland.

Figure 1: Contribution of deep-sea shipping to Switzerland’s intercontinental import and export

Maritime Shipping Often Unavoidable

In intercontinental trade as well as for intra-European transport chains, ships are often unavoidable. The transport between states has developed very dynamically over the last 50 years due to standardized containers. Especially because of the enormous transport capacity and the associated cost efficiency, air freight can only compete with deep-sea shipping in exceptional cases. Only for very high-value, time-sensitive, or perishable goods is air transport chosen in international trade. The essential volumes, such as liquid and dry fuels or machine parts, vehicles, and other goods have always been transported by container ships, bulk carriers (bulkers and tankers), or roll-on/roll-off ships (RoRo) between international seaports.

Without Maritime Shipping, It’s Not Possible

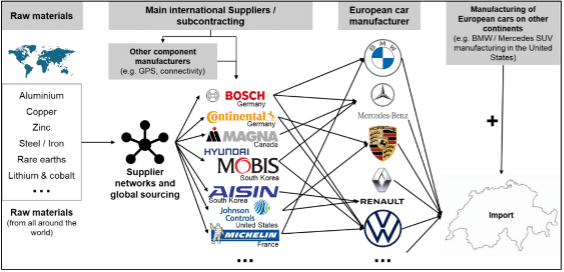

The current LAE study concludes that in international trade, i.e., between Switzerland and non-European countries, between 90% and 95% of imports and exports are at least partially transported by sea (see Figure 1). When considering the entire process chain of imported and exported goods, one can assume an even stronger dependence of imports and exports on deep-sea shipping. When examining imports of vehicles from European countries, such as vehicles from France or Germany, the dependence on deep-sea shipping becomes evident. Due to the multitude of actors, trading partners, and production steps, the process chains are not only opaque for end customers but also difficult to trace (see Figure 2). The representation of possible supplier networks in the automotive industry is thus just one of many illustrative examples.

Figure 2: Complexity of global supply chains – Example automotive industry

North Sea Ports and Rhine Connection Remain Crucial for Foreign Trade

Despite the geographical proximity to the Mediterranean, a large part of the trade flows relevant to Switzerland is still handled through the North Sea ports. In addition to the Port of Hamburg, the ports of the ARA range (Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Antwerp) are particularly important for Switzerland. Especially Rotterdam, with its direct inland shipping connection via the Rhine to Basel, is considered an important transshipment port for the transport of liquid and dry bulk goods such as refined oil, grain, or construction materials. In container traffic, further growth is expected, especially through the European North Sea ports. Transshipment capacities in the Swiss Rhine port are thus an important component for multimodal transport in, out, and through Switzerland.

Silk Road Remains a Niche

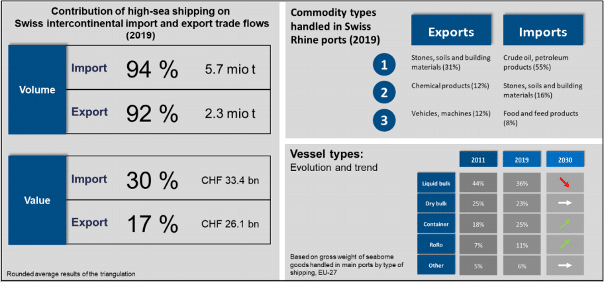

Figure 3: Symbolic loading of containers onto the rail

The new Silk Road, consisting of deep-sea ports, transshipment terminals, and thousands of kilometers of rail from China to the world, is repeatedly referred to as a serious competitor to international maritime shipping. Last year, the transport volume was increased by 500,000 TEU. A growth of 20% is expected for 2021. However, in the medium term, only 1 million 20-foot standard containers are to be transported. In contrast to the current total transshipment of 46 million containers in the European North Sea ports, the transported container volume on the new Silk Road is thus negligible. The comparison becomes particularly striking when one imagines that all nearly 24,000 20-foot containers (TEU) of the fully loaded MSC Gülsün would result in a train length of about 340 km if loaded onto the rail (see Figure 3). Furthermore, there are still insufficient transshipment capacities between Central Europe and Asia. Missing transport capacities and the unfavorable infrastructural conditions currently hinder a successful shift of transport capacity to the Silk Road.

Less Bulk Goods – More Containers?

The direction is clear – goods transport will continue to shift towards container shipping. The growth in ship sizes and the associated economies of scale for their operation lead to decreasing transport costs per container with constant demand. An unusual development is also emerging for both liquid and dry bulk goods: these are being transported more than ever by container. According to expert opinion, this is a logical consequence, as the container does not require special loading and unloading infrastructure – specific storage areas can also be dispensed with (see Figure 4). A decreasing demand for liquid and solid fossil fuels is also expected. For grain, feed, or construction materials, no sustainable shifts are anticipated. Only in the short term could slight changes occur due to regional export restrictions on transport volumes by sea. The Russian Federation recently reduced export volumes for grain to secure the supply of its own society. Consequently, Switzerland must import from overseas – by sea!

[caption id="attachment_9474" align="alignleft" width="604"] Figure 4: Contribution of deep-sea shipping to Switzerland’s intercontinental import and export, commodity groups, and ship types

Figure 4: Contribution of deep-sea shipping to Switzerland’s intercontinental import and export, commodity groups, and ship types

Focus on Hinterland Connectivity

For the use of Mediterranean ports by the Swiss Confederation, a reliable connection with sufficient capacity is essential. Despite numerous infrastructure projects within Switzerland, such as the NEAT, there is still a need to tap considerable potentials through the development of intermodal capacities, especially in Italy. However, suitable infrastructures within Switzerland will also be of paramount importance in the future. One such example is the Basel Gateway Nord terminal, which significantly increases intermodal transshipment capacities and thus creates added value for the entire region.

© Leon Zacharias

Leon Zacharias

is a trained shipping merchant and a master’s student at the University of St. Gallen. As a project employee, he works at the Institute for Supply Chain Management (ISCM-HSG) and at Logistics Advisory Experts GmbH.

Leon.zacharias@logistics-advisory-experts.ch

www.logistics-advisory-experts.ch

© Ludwig Häberle

Ludwig Häberle

works as a project manager at Logistics Advisory Experts GmbH and is a research associate and doctoral candidate at the Institute for Supply Chain Management at the University of St. Gallen.

Ludwig.haeberle@logistics-advisory-experts.ch

www.logistics-advisory-experts.ch